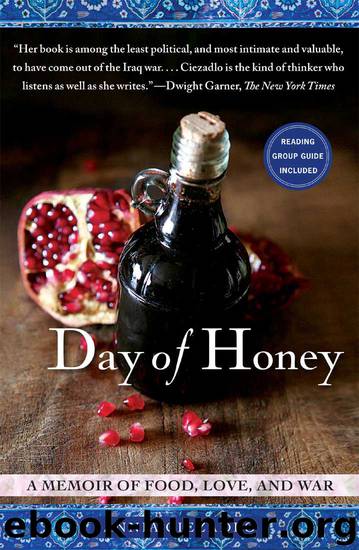

Day of Honey: A Memoir of Food, Love, and War by Annia Ciezadlo

Author:Annia Ciezadlo [Ciezadlo, Annia]

Language: eng

Format: azw3, mobi

Publisher: Free Press

Published: 2011-02-01T05:00:00+00:00

The next day was hot and humid. Over strenuous objections from his wife, Abu Hassane walked to the neighborhood pharmacy to pick up some medicine. He collapsed outside the pharmacy and hit his head on the sidewalk. The pharmacist called an ambulance, which rushed him to the hospital, but although he was conscious, he couldn’t speak. A few days later he went into a coma.

Mohamad and I spent the next few weeks at the hospital, along with a constantly rotating cast of aunts and uncles, cousins, friends, and distant relatives. One night, Mohamad came home so angry that he could barely speak. He had spent all day navigating Lebanon’s health care bureaucracy: Abu Hassane was covered by the state-run medical insurance, and since the Lebanese government did not pay its bills, the top hospitals wouldn’t accept its insurance. When he finally got to the hospital, a distant cousin sidled up to him and said, “I was here at the hospital this morning, and you weren’t. Where were you?” To the sanctimonious cousin, Mohamad’s brief absence proved that he was a bad son and made for a prize morsel of gossip—exactly the kind of toxic family rumor that had made our Post-it Note marriage necessary.

“Now I know why this country is so dysfunctional,” he raged. “Because we spend all our time doing stupid, useless things just so people won’t criticize us. Why do we have to do all these stupid things?”

I patted the bed and held up the blanket so he could get in. “Most of your family is nice, though,” I said.

“And this is why Lebanese people who go abroad get so much more done,” he said, climbing into bed, still furious. “Because they’re freed of the yoke of their families!”

All of our young Lebanese friends had the same problem. Everyone loved their families, their traditions. But “tradition,” in the hands of certain relatives, became a venomous form of emotional blackmail. Aunts and uncles would call up their siblings and insinuate that they were bad parents if a daughter or a son remained unmarried. Competitive cousins would smear one another with vicious innuendos. And a shocking number of families—Christians as much as Muslims, in my experience—would ostracize sons or daughters who dared to fall in love outside their sect. There was no escape from the malevolent schadenfreude of the extended family.

I hugged him. Since his father’s collapse, he had come home in a rage every night: at meddling relatives, at the state-run medical system, at Lebanon. All of it perfectly legitimate, but all of it beside the point, which was that his father was dying.

Download

Day of Honey: A Memoir of Food, Love, and War by Annia Ciezadlo.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Biscuits: A Savor the South Cookbook by Belinda Ellis(4329)

The French Women Don't Get Fat Cookbook by Mireille Guiliano(3651)

A Jewish Baker's Pastry Secrets: Recipes from a New York Baking Legend for Strudel, Stollen, Danishes, Puff Pastry, and More by George Greenstein(3586)

Ottolenghi Simple by Yotam Ottolenghi(3583)

Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook by Better Homes & Gardens(3580)

Al Roker's Hassle-Free Holiday Cookbook by Al Roker(3527)

Trullo by Tim Siadatan(3422)

Bake with Anna Olson by Anna Olson(3397)

Hot Thai Kitchen by Pailin Chongchitnant(3378)

Panini by Carlo Middione(3330)

Nigella Bites (Nigella Collection) by Nigella Lawson(3226)

Momofuku by David Chang(3183)

Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking by Nosrat Samin(3138)

Modern French Pastry: Innovative Techniques, Tools and Design by Cheryl Wakerhauser(3138)

Classic by Mary Berry(3010)

Best of Jane Grigson by Jane Grigson(2994)

Tapas Revolution by Omar Allibhoy(2976)

Solo Food by Janneke Vreugdenhil(2967)

Ottolenghi - The Cookbook by Yotam Ottolenghi(2929)